INTRODUCTION

Right now, student journalism is in trouble. Between censorship laws, distrust in the media and the unknown impact of Artificial Intelligence, the understanding of law, ethics and new literacy is of paramount importance.

Right now, student journalism is in trouble. Between censorship laws, distrust in the media and the unknown impact of Artificial Intelligence, the understanding of law, ethics and new literacy is of paramount importance.

Keeping this material in mind is the responsibility of each individual journalist, but creating awareness and advocating for accurate and objective news is critical to the journalism industry. In addition to providing ethical journalism at McCallum, I am committed to educating my community on these issues and teaching my staff to do the same.

LAW

To be the editor-in-chief, I quickly learned, you need to be the last line of defense. The expert on everything journalism. If a staffer had a question about how to do something, you better be equipped with the information to help them out.

In my mind, this meant understanding camera settings, lede writing techniques or how to make cutouts. While I felt confident in my ability to answer such questions, I didn’t realize there was a whole other side to running a student publication — the legal side. Throughout my time as EIC I strived to not only understand the laws that student publications must abide by but to involve my staff in the process.

Censorship laws

Texas is not a New Voices state.

“How have I never heard of this?” I wonder as I pour over the Student Press Law Center (SPLC) website.

It’s the summer before junior year. I’m attending the Gloria Shields NSPA Media Workshop, studying Editorial Leadership. I expected to learn about team building or feedback techniques — information that would serve me well as the incoming editor-in-chief of The Shield.

Instead, I learned this:

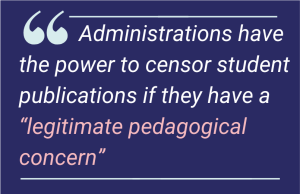

Because of the 1988 Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier Supreme Court case, administrations have the power to censor student publications if they have a “legitimate pedagogical concern” — vague language that created a loophole for schools to practice arbitrary censorship. In response, New Voices, a student-run grassroots movement to restore student press rights state-by-state across the country, began. Texas is not one of the 17 states where student press censorship is prohibited.

Because of the 1988 Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier Supreme Court case, administrations have the power to censor student publications if they have a “legitimate pedagogical concern” — vague language that created a loophole for schools to practice arbitrary censorship. In response, New Voices, a student-run grassroots movement to restore student press rights state-by-state across the country, began. Texas is not one of the 17 states where student press censorship is prohibited.

Fortunately, McCallum has a supportive team of administrators who champion the rights of students to free expression. However, I know that is not the case for most schools in Texas. Because of this, I have tried to use my knowledge of New Voices laws to advocate for schools across the state facing student press censorship.

New Voices Texas

In June of 2023, I was selected as the Legislative Officer and Education Specialist for New Voices Texas to continue to fight for a free student press in my state.

In June of 2023, I was selected as the Legislative Officer and Education Specialist for New Voices Texas to continue to fight for a free student press in my state.

However, my work as an officer has differed greatly from last year’s legislative officer. This is because of the way the Texas Legislature was set up 1846 — a time when Texas’s size made it difficult for lawmakers to travel all the way to Austin to meet yearly. Thus, a system in which the legislature goes into session for only 140 days every two years was written into the state constitution.

Because of this, making progress with Texas Legislation is no easy task. Even if I had worked with New Voices for the entirety of my time in high school, there would have been only two opportunities for NVT to try and pass a New Voices bill.

And unfortunately, this year is not a legislative session year for Texas, which has limited the work I can do as NVT’s Legislative Officer. So instead, I’ve focused most of my efforts on outreach and education that will hopefully lay the groundwork for NVT success in next year’s session.

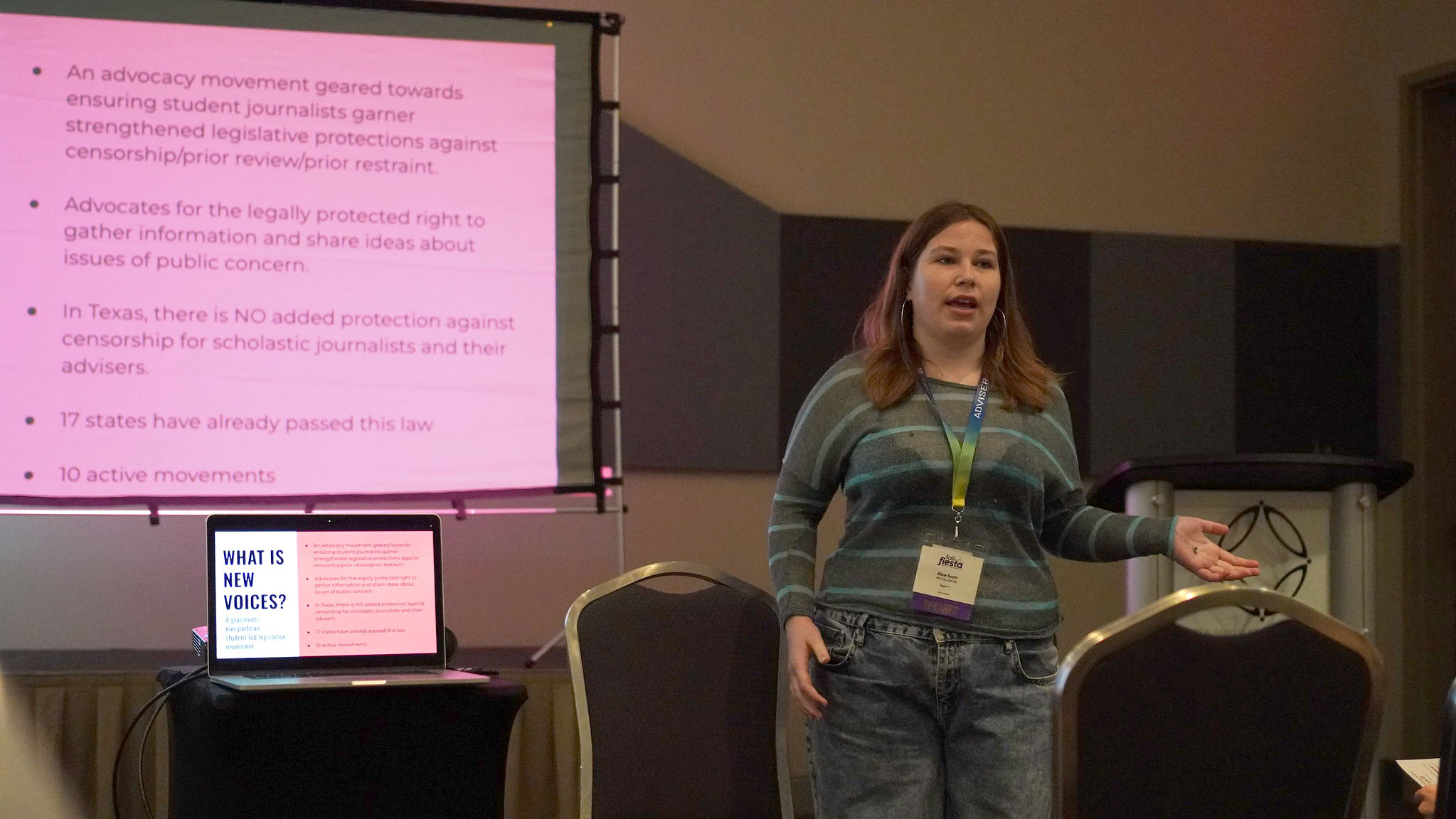

Last fall alongside NVT’s Legislative Specialist Ella Carter, I gave a presentation at the 2023 TAJE Fall Fiesta state convention about the basics of the New Voices movement and why it exists. After our presentation, we were joined via Zoom by Hillary Davis, an SPLC employee who specialized with New Voices work. She supplemented our session with the national context of New Voices.

This presentation informed the wider scholastic journalism community in Texas about NVT efforts and got involvement from students across the state.

Most recently, I created resources for the sixth annual Student Press Freedom Day. This event, hosted by the SPLC, took place on Feb. 22 and was a major opportunity for New Voices Texas to spread awareness about the movement so that we will have a larger coalition of schools and students who will help advocate for a New Voices law next year when Texas goes into Legislative Session.

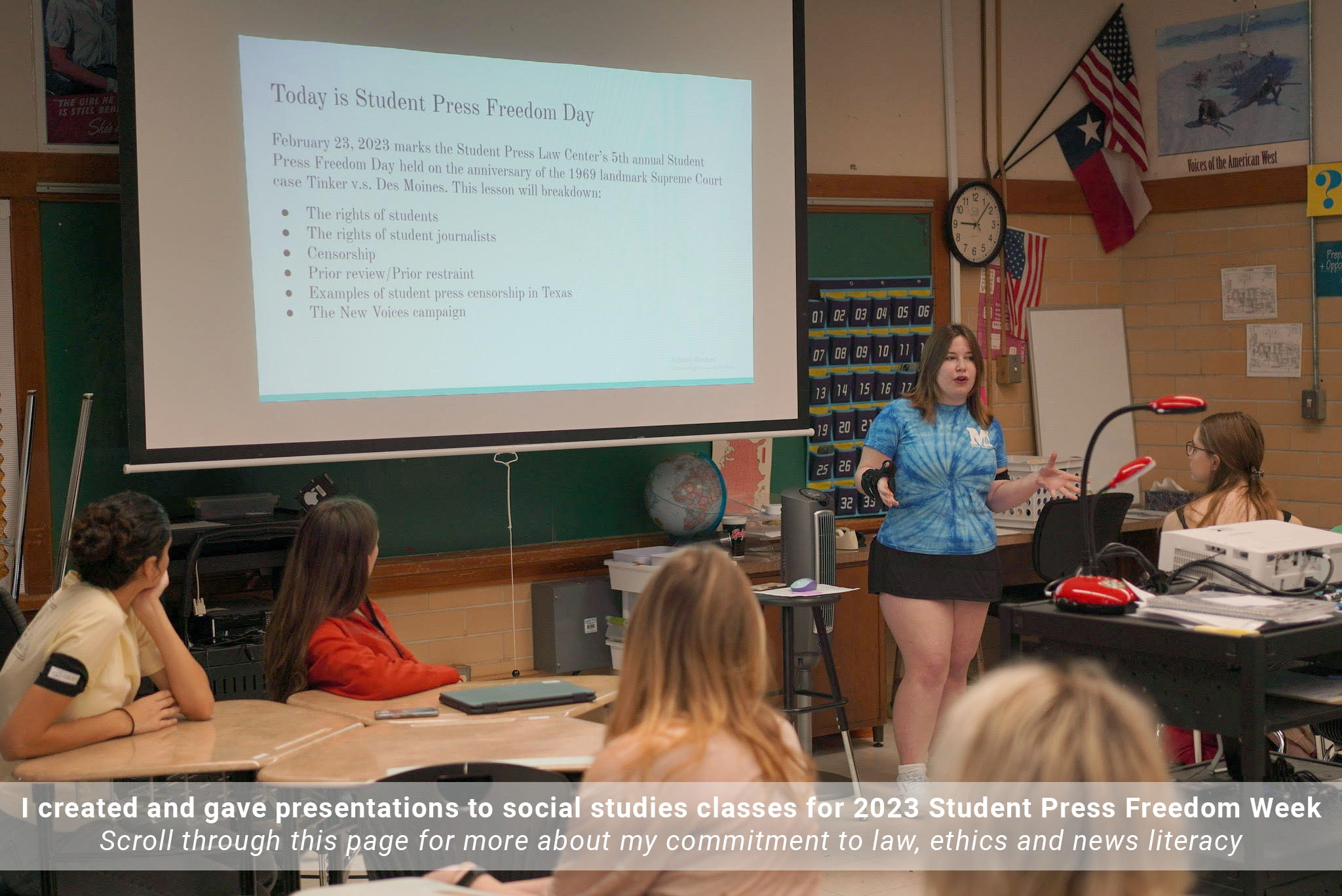

I combined my knowledge of the law as Legislative Officer and my resources as an Education Specialist to help create a comprehensive presentation and a resource guide that is available on the NVT website for student publications to use to talk about New Voices and censorship at their schools. The presentation is modeled after the one I created last year for a weeklong news literacy campaign I did on campus that overlapped with Student Press Freedom Day.

To learn more about the Student Press Freedom Week campaign that I held at McCallum in the spring of 2023, scroll to the News Literacy section of this page.

Copyright law

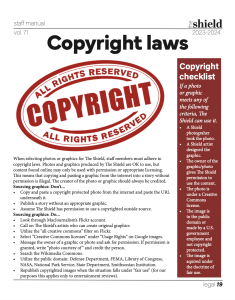

When I was first taking on the role of editor-in-chief, I was struck by how much of my knowledge, which seemed like the “common sense” of scholastic journalism, was not inherent to new staffers. And while I was in a rush to teach key skills like writing, photography and design, it didn’t immediately occur to me that these “inherent” rules of journalism, like copyright law, needed to be taught.

Teaching copyright law

My initial approach to teaching copyright law was on a case-by-case basis. Whenever a staffer approached me about finding a graphic, I took it as an opportunity to explain how copyright and fair use worked. However, this allowed some staffers to slip through the cracks.

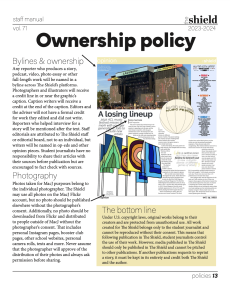

So, the summer before my senior year, as I was creating a staff manual that would include all necessary resources and policies for Shield staffers, I knew I needed to touch on copyright. In the “Legal” section of the staff manual, I created a page with information about how copyright law works as well as a checklist that staffers could look back at to confirm that the graphic or photo they wanted to use would not be infringing on copyright law.

I made sure to incorporate discussion of copyright into the “Ownership policy” page so that staffers understood that they own the rights to the work they create while on staff — not The Shield. This ensured that I was not only teaching my staffers to adhere to copyright laws when selecting graphics but also explained that they too have rights regarding the work they create for The Shield.

To learn more about how I created The Shield staff manual, navigate to the Editing, Leadership & Team building page.

Handling copyright issues

During my junior year, my co-EIC and I decided that our third issue of The Shield would center around environmental issues. As staffers got to work on their stories, we got to work planning the cover. Our initial idea was to create a graphic that used imagery from The Lorax (which is used in McCallum’s AP Environmental Science class to teach sustainability).

However, this posed an issue. The artwork would be student-created, but the character of the Lorax was under copyright. I’d seen different student publications adapt cartoons such as “Oh the Places You’ll Go” and “The Giving Tree” into graphics, so it was unclear whether creating a Lorax graphic was legal or not.

Click through the presentation below to see what I did.

Not all permission requests I’ve made have been so complicated. Often when The Shield needs photos for news stories that MacJ photographers just can’t get, we’ve reached out to local news outlets and requested permission to use their photos. Last year, for our first issue, we wanted our news briefs page to center around local elections. We needed photos of Texas’s two gubernatorial candidates, Greg Abbott and Beto O’Rourke to go on the page, so I reached out to the Texas Tribune to request featured images used in “Gov. Greg Abbott leads Beto O’Rourke by 5 percentage points in new poll” and in “TribCast: Greg Abbott and Beto O’Rourke enter the homestretch.”

Ethics

It’s no secret that journalism and the news is not always positively perceived by the public. If journalists are doing their job right — holding people in power accountable and uncovering the truth — they are always going to make certain groups of people upset. But right now, the perception of journalists is at an all-time low. In fact, American trust in mass media has been on a steady decline since 1976, currently sitting with only 34% of Americans having a “great deal/fair amount” of trust in the media, according to Gallup.

It’s no secret that journalism and the news is not always positively perceived by the public. If journalists are doing their job right — holding people in power accountable and uncovering the truth — they are always going to make certain groups of people upset. But right now, the perception of journalists is at an all-time low. In fact, American trust in mass media has been on a steady decline since 1976, currently sitting with only 34% of Americans having a “great deal/fair amount” of trust in the media, according to Gallup.

This perception is hard to fight, so I’ve made it a priority to ensure that The Shield follows ethical staff policies and acts ethically in divisive situations. While we can’t solve the public distrust in the media, acting as ethical staff helps build a better reputation for journalism as an industry.

Building an ethical staff

To follow through on this goal of holding The Shield to professional ethical standards, I had to go beyond just making sure I was following ethical practices. I had to integrate ethics into the policies, training and practices of the entire Shield staff. Continue reading to learn about exactly how I made ethics a priority at my publication.

Creating ethical staff policies

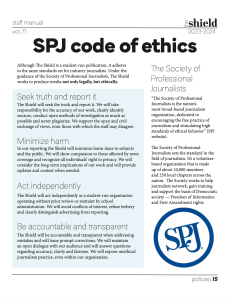

When I was creating the staff manual, another key component to was clarifying staff policies. I wanted to make sure that I was holding The Shield to not only the legal standards of industry journalists but also the ethical standards. So I turned to the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics to help guide me. Click through the following photo gallery to see how I integrated the four main tenets of the SPJ Code of Ethics (seek truth and report it, minimize harm, act independently and be accountable and transparent) into The Shield staff policies.

- Seek truth and report it – Yellow

- Minimize harm – Pink

- Act independently – Green

- Be Accountable and Transparent – Blue

Teaching ethics

Teaching ethics

Creating ethical policies for The Shield to follow was only one piece of the puzzle in building an ethical staff. Written policies were meaningless without buy-in from staff members. And to get buy-in, I needed staffers to understand why it is important for journalists to follow an ethical code.

The first way I taught ethics to my staff was by creating a resource page within the staff manual that explained the SPJ code of ethics. I put the code of ethics in terms of how The Shield adheres it to make it more relevant to staffers.

I also created the following presentation that went more in-depth into the logistics of image ethics. While our staffers were not struggling to understand the basics of the SPJ code of ethics, there were details that the editors and I really didn’t touch on. So, I used what I learned about photo ethics from the Medill-Northwestern Journalism Institute to put this lesson together for my staff.

What I like about this presentation is that it teaches critical skills through a discussion format. Instead of just pointing out why what the photo editors did wrong, I asked the staff what they thought was wrong with the way the images in the case studies were altered. While I later backed up everything that we discussed with the NPPA’s statement on editing photos, this conversation-based format helped develop the buy-in I was trying to develop. Having staffers come to conclusions on their own about why altering images can be harmful and not journalistic (instead of just telling them) was a much more meaningful way to ensure that they did not engage in unethical practices.

Handling ethics issues

While incorporating ethics into staff policy and class lessons is valuable, none of it matters if there isn’t follow through when real issues of ethics occur. As editor-in-chief, I have made it a priority to put ethical policies into practice when issues arise. Take a look at an example of one such occurrence.

Hate group agitators disrupt the school day

This past September a hate group protested on the sidewalk outside of McCallum during the last period of the day and into dismissal. Because the newspaper room is only steps away from the school’s main entrance, The Shield staff was some of the first students to hear the hate speech being shouted through a megaphone by protesters right outside our school. We had a few reporters run out to photograph the event and many staffers began researching the group’s history. We had to cover this. But quickly, a new question arose. How?

The usual way that we cover breaking news involves posting photos of the event on Instagram with an in-depth caption that includes at least one interview with key stakeholders followed later by a full-length news story.

But in this case, we were hesitant to post pictures of the demonstration. We did not want to republish hate speech that could be harmful to some of our readers. Similarly, we did not want to name the group or link to their video because we did not want to give them a platform to spread hate. At the same time, we didn’t want to diminish the severity of the situation or alter the reality of what happened. We had to figure out a way to fully report the truth without causing any further harm.

So, before the end of the period, the fellow EICs and I decided that the best way to determine how to cover this breaking news was to discuss with the staff. We had reviewed the SPJ code of ethics only a few days before when we passed out staff manuals, so we decided to use this real-life moment as a teaching opportunity. Here’s how we explained the situation to the class:

- We told them we needed cover this incident as soon as possible because it is breaking news that is relevant to all McCallum students and parents.

- We have photos of the protestors, but they include the group’s signs which had both written hate speech and misinformation on them.

- We have the name of the group and the link to the group’s YouTube channel where they are live-streaming the “preaching” they are doing at McCallum.

- We want to act as ethical journalists by both maximizing truth and minimizing harm.

As a staff, we decided to write a full-length caption with an interview from administration. Instead of posting the caption with images from the protest, we posted it with a breaking news graphic that included a quote from principal Andy Baxa. We did name the group of protesters, as it seemed irresponsible to not include such a key fact, but we did not link to their videos or website. We agreed this was the best way to seek truth and report it without causing unnecessary harm.

We were pleased to find out that when KXAN later covered the event, they also did not include any footage of the event as it is part of their editorial policy to not reproduce hate speech.

In all further coverage of the event, we published only photos of the parent and student response to the demonstrators which included sidewalk chalk decorations with supportive messages and LGBTQ+ pride symbols and parents gathering outside McCallum with pride flags and signs.

In all further coverage of the event, we published only photos of the parent and student response to the demonstrators which included sidewalk chalk decorations with supportive messages and LGBTQ+ pride symbols and parents gathering outside McCallum with pride flags and signs.

About a month later, an editor from The Harbinger, the student publication at Shawnee Mission East High School, reached out to me and asked if they could republish one of our photos of the event for the national news coverage in their first issue of the year. Once again, I passed along photos of the parent/student response, rather than the protest.

Eventually, when the full in-depth news story came out, we used one photo of the protest because the writing on the signs was blurred and the focus was not on the agitators. The photo was also not the story’s featured image.

NEWS LITERACY

While The Shield always works to keep the community informed, as editor-in-chief, I made it a goal to educate my school community beyond just articles written, so I decided to use my platform to spread awareness about the state of student press censorship in Texas.

The Student Press Freedom Week Campaign

After learning that The Shield, like other school news programs in Texas, could be subject to administrative censorship, I had a new drive stepping into the role of editor-in-chief. This was an issue that few members of our news staff, and even fewer members of our school community, were aware of. So I reached out to the McCallum principal Nicole Griffith seeking permission to teach my fellow students about press freedom and their rights through a weeklong news literacy campaign.

I created the presentation below that detailed the relevant issues surrounding student press freedoms and shared it with Ms. Griffith. We decided social studies was the best class to present this information in, and she connected me to the school’s social studies department chair, Clifford Stanchos. Mr. Stanchos shared my lesson plans with the history department and teachers signed up to have guest speakers from the MacJ team on Feb. 23, Student Press Freedom Day, and on Feb. 24.

After coordinating with teachers, I trained staff editors from the newspaper staff to be guest presenters. Then I created a schedule so teachers knew who to expect each period and presenters were not overworked. Ms. Griffith agreed to excuse absences for staffers who were presenting, but I also created permission forms/passes for student lecturers to keep teachers in the loop.

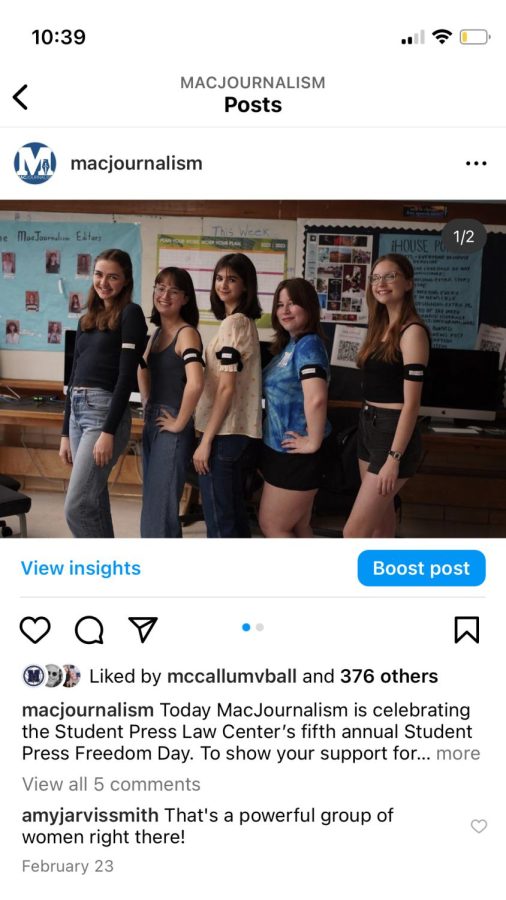

Next, I hand-created 500 black armbands as an homage to those used in the landmark Tinker v. Des Moines victory for student First Amendment rights. Tinker was the 1969 Supreme Court case that famously ruled that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate” in the case of two high school students who were suspended for school for wearing black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. The goal of the New Voices movement is to return student media to the “Tinker standard,” so the armbands were meant to serve as a reminder of what we were fighting for.

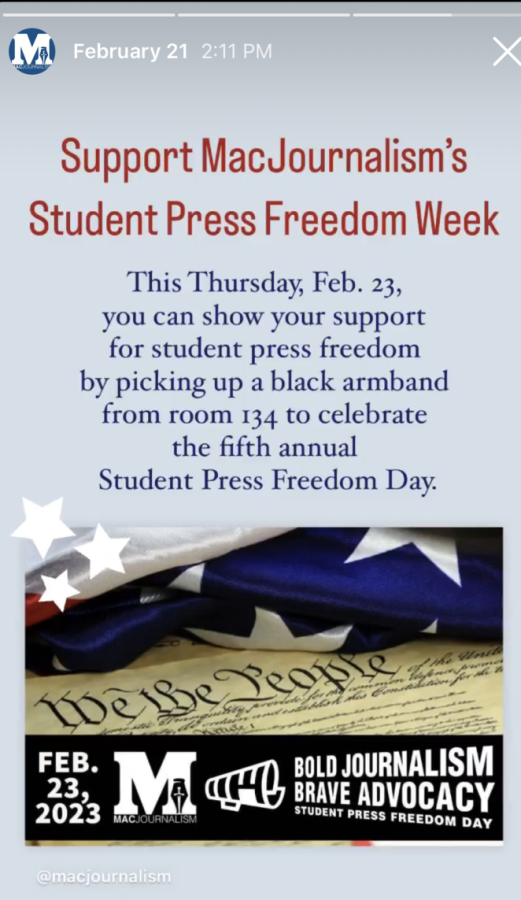

With the on-campus activities planned, I switched gears to focus on the social media aspect of the campaign. Student Press Freedom Week kicked off on Feb. 20, with an Instagram post detailing the precedent-setting Supreme Court case Tinker V. Des Moines that solidified students’ rights to free speech at school. Each day I wrote and shared an Instagram post about different aspect of Student Press Freedom Week. Scroll through the gallery below to read each post. Note: The fourth post was a promotional post to encourage students to pick up black armbands from the newspaper room and does not contain an informational caption about student press freedom week like the other five.

Although the Instagram campaign ran through the entire week, the main event was the presentations that took place on Thursday (Feb. 23, SPLC’s Student Press Freedom Day) and Friday (Feb. 24, The Tinker v. Des Moines anniversary). This is where the black armbands came into play. Staffers came in early on Feb. 23 and 24 to help set up the armbands in the newspaper room. We also used Instagram to promote the armbands that I created for students and teachers to wear to show their support for student press freedom. Information about where to pick up armbands was shared via Instagram through both 24-hour stories and static posts. Each armband was hand-created with an iron-on patch, available in the newspaper room and distributed during presentations.

The gallery below includes adults and students from the McCallum community who showed support for student press freedom by wearing black armbands.

Since not all social studies teachers were able to work in a guest presentation, I recorded the presentations, then edited and posted them as Reels via Instagram to ensure that everyone who wanted to learn more about this issue had the opportunity to. Utilizing Reels allowed us to implement multimedia content into the campaign to showcase the work we were doing in a different format. And while posts can get lost in our feed, Reels were more likely to show up on our followers For You pages. Below are three of the reels created from presentations given on Feb. 23. All 11 Reels that I created can be found at our @macjournalism Instagram account.

One of the most valuable aspects of the campaign was that Principal Nicole Griffith signed the New Voices Texas Administrator Pledge, committing to supporting a free student press on the McCallum campus. My co-editor, Evie Barnard and I also signed the NVT pledge, signifying The Shield’s support of the New Voices and their movement. The editor-in-chief of The Knight, Charlie Partheymuller also signed the publication pledge on behalf of the yearbook staff.

As the campaign came to a close, I converted our week-long social media content into a web post to make it easy to find all the information in our online publication. In the weeks that followed, both my adviser, Dave Winter and I received thanks and compliments for putting on the event. It was clear that students and staff on campus appreciated the work we did. But, one of the best parts about this campaign was that everything we did was accessible online. The results we saw from our social media analytics (shared below) helped solidify that this campaign was not just influential for those on campus, but the greater McCallum community.

Presenting at SXSW EDU

In the spring of 2023, Shield staffers were invited to join PBS Student Reporting Labs at the SXSW EDU conference. We were instructed to bring work that we had done to present at SRL’s sharing session which involved breakouts with other student journalists and industry professionals who attended the event.

In the spring of 2023, Shield staffers were invited to join PBS Student Reporting Labs at the SXSW EDU conference. We were instructed to bring work that we had done to present at SRL’s sharing session which involved breakouts with other student journalists and industry professionals who attended the event.

We decided to speak about the work we had just done for Student Press Freedom Week. We brought sample black armbands, the presentation given to social studies class and pulled up the Instagram posts on a laptop to explain how we executed the news literacy campaign and why it was important.

This presentation was an opportunity to further the reach of the New Voices movement beyond just students. Quite a few of the adults attending the event were teachers looking to start a news program and were unaware of the state of student press rights in the U.S. and Texas.

Because student press censorship is such a student-centric issue, it was meaningful to spread awareness to a different community that could help advocate for scholastic journalists. And even though presenting at SXSW in no way solved the problem of student press censorship, it gave further exposure to a generally unknown issue — and considering the limiting nature of the Texas Legislature, sometimes exposure and building connections is the most important thing I can do.

Because for every story The Shield publishes that isn’t subjected to censorship, there are stories across the country that are. Each time that happens, student writers are being taught that a free press isn’t essential.

I wouldn’t be doing my job as a journalist if I wasn’t working to stop misinformation.

FINAL THOUGHTS

It would be very easy to put together a portfolio of work and not include the category of law, ethics and news literacy, because those are topics that a lot of journalists at the high school level take for granted. They rely on their advisers to fill in the blanks concerning the legal issues that arise when producing a publication.

And in all honesty, if you’d asked me three years ago what I would have spent the greater part of my time as editor-in-chief focusing on, I never would have guessed it would have revolved around the rights of student journalists or understanding ethical reporting.

But for me, leading a publication meant that I had to dig into the minutia — the fine print. I was never going to be satisfied by focusing my leadership just on creating the best possible product if the product wasn’t created responsibly and with integrity. Because student journalism should always be about responsible journalism.